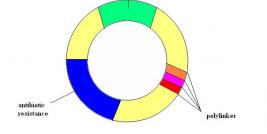

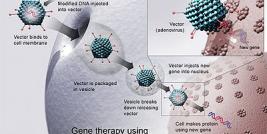

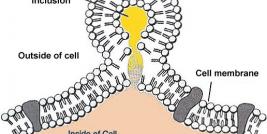

Cancer Research UK scientists have for the first time developed a treatment that transports 'tumour busting' genes selectively to cancer cells, according to a study published online in Cancer Research*. Using nanotechnology, the researchers were able to package anti-cancer genes in very small particles that directed the treatment selectively to tumours in mice so that it was only taken up by cancer cells, leaving healthy cells unharmed. Once taken up by cancer cells, the genes enclosed in the nanoparticles force the cell to produce proteins that can kill the cancer.

In this study the cells were forced to make a protein which was then visible in whole-body scans of the mice revealing that healthy cells were not affected by the treatment. Previous studies showed that the type of gene therapy used in this study can shrink tumours and even cure around 80 per cent of the mice given the treatment. This type of technology is particularly relevant for people with cancers that are inoperable because they are close to vital organs, like the brain or lungs. These cancers are often associated with poor survival. Now scientists have found a particle that can be used to selectively target cancer cells, they hope nanotechnology can be extended to treat cancer that has spread.

Study author Cancer Research UK's Dr Andreas Schatzlein, based at the School of Pharmacy in London, said: "Gene therapy has a great potential to create safe and effective cancer treatments but getting the genes into cancer cells remains one of the big challenges in this area. This is the first time that nanoparticles have been shown to target tumours in such a selective way, and this is an exciting step forward in the field. "Once inside the cell, the gene enclosed in the particle recognises the cancerous environment and switches on. The result is toxic, but only to the offending cells, leaving healthy tissue unaffected. "We hope this therapy will be used to treat cancer patients in clinical trials in a couple of years."

Traditional chemotherapy indiscriminately kills cells in the affected area of the body, which can cause side effects like fatigue, hair loss or nausea. It is hoped that gene therapy will have fewer associated side effects by targeting cancer cells. Dr Lesley Walker, Cancer Research UK's director of cancer information, said: "These results are encouraging, and we look forward to seeing if this method can be used to treat cancer in people. Gene therapy is an exciting area of research, but targeting genetic changes to cancer cells has been a major challenge. This is the first time a solution has been proposed, so it’s exciting news."