How “The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It” Wrote Itself.

When I met smiling, 9-year-old Corey Haas on a dazzling Saturday morning in early December, 2009, I knew that the time had finally arrived to write a gene therapy book for the general public. St. Martin’s Press published “The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It,” in March, 2012. It was a long time coming – as was the field of gene therapy itself.

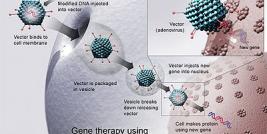

I’d been writing about gene therapy since the beginning. In September 1990, at the NIH, 4-year-old Ashi DeSilva received her own altered white blood cells to treat ADA deficiency. Two other Septembers form the high and low points of my book: Corey’s amazing ability to see at the Philadelphia zoo, four days after gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis type 2 in 2008, and 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger’s death, four days after his gene therapy to treat ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, in the same city in 1999.

Before Corey, I’d envisioned the book to be about a boy with Canavan disease whom I’d been writing about in my textbook, “Human Genetics: Concepts and Applications” (McGraw-Hill Higher Education) since the fifth edition, published in 2003. At that time Max Randell, age five, had had two gene therapies, and he enjoyed good mobility. With each new edition of the textbook, I’d contact his mom, hoping he was still okay. (He is.)

But Canavan disease slowly robs a child of all movement – even with gene therapy. I was subconsciously waiting for a more positive outcome, especially in the wake of the leukemia cases that arose in the SCID-X1 trials when the retroviral vector targeted an oncogene. I couldn’t even imagine a story as phenomenal as Corey and his vanquished LCA2.

So after meeting the symbolic “boy who saved gene therapy,” I e-mailed a two-paragraph query to a long list of literary agents, beginning with “On a bright September Sunday in 2008, 8-year-old Corey Haas approached the Philadelphia Zoo, looked up, and screamed – it was the first time he’d seen the sun.” Ten minutes into my effort the positive responses began to pour in, and all the agents offered the same advice: the kids other than Corey shouldn’t be stuffed into one chapter, but each given his or her own. They ARE the story.

As my agent and new editor talked contracts, ”The Forever Fix” began to write itself.

Corey’s story flowed easily, as did the history. Then I read about the Salzman sisters and added a chapter on their family’s disease, adrenoleukodystrophy. It added perspective to what Corey’s family, who found themselves in the right place at the right time to enter a clinical trial, didn’t have to face. Next the book contrasts a family on the brink of gene therapy (another 8-year-old, Hannah Sames, for the ultra-rare giant axonal neuropathy) with the Canavan families, including Max, to explore the aftermath of gene therapy. The book concludes with the continuation of Corey’s story: his gene therapy at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Drs. Jean Bennett (“Dr. Jean”) and Al Maguire (“Dr. Al”) led the clinical trial, and are about to start phase 3.

Powerful themes emerged as I wrote the book: the value of animals in research (sheepdogs for LCA2), pioneering women scientists, the incredible efforts of families with rare diseases, and informed consent and the clinical trial process.

The most magical part about writing the book happened when the chapters – distinct in my proposal – began to interweave. They shared researchers, such as Jim Wilson, Guangping Gao and Paola Leone. And then the shared stories happened in real time: Hannah’s mom Lori Sames stood watching at the annual meeting of the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy as Corey and Dr. Jean bantered onstage, the tears flowing as she thought of her young daughter. The next morning, I took her, Corey’s family, and Dr. Jean out to breakfast, where the researcher connected me with French Anderson, one of the founders of the field. The journey came full circle.

“The Forever Fix” is narrative nonfiction – not my usual textbook fare, nor a technical work. It’s meant for the many people who are afraid of science. The title comes from Lori Sames. At a fundraiser, she turned to me, tears in her eyes as she watched well-wishers carry Hannah around the room, and said, “Ricki, if gene therapy works, it’ll be a forever fix.”

I think she’s right.

For further info:

https://www.amazon.com/author/rickilewis